|

| Images: Canva |

I live not far from an Army base at the southern end of New Zealand's North Island - Trentham Military Camp. It was the staging post for many of our country's deployments of troops to World War One’s battlefields, a hemisphere away.

The First World War is still an enigma to me, confined to the kitbag of inexplicable matters, alongside why men have nipples. (The reasons for a Second World War can be explained relatively easily - a sociopathic, racist, genocidal madman decided that he had the right to wreak havoc in Europe and kill millions of people in the process while punishing those countries who punished Germany for starting the First World War.)

I didn't study history at school, so taught myself the art of shining light into the past’s musty corners. What I found out about the origins of WW1 was that in the decades leading up to it, two groups of nations had formed sides (much like in ‘Bullrush’, the schoolyard game I played as a boy). On the goodies team were the UK (and its empire), France, and Russia (the Entente powers) with Italy and the US piling on later. On the dark side were Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire (Turkey). By August 1914, the name-calling and tongue-poking-out between the two groups of countries and their proxies had markedly deteriorated. A full-scale punch-up erupted when the German side took umbrage at the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria and the rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

|

| Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty. Credit: Wikimedia Commons |

The campaign proved to be a disaster for the Entente powers. The only success they had was when they vacated the peninsula without casualties in January 1916, nine months after the landings. The Ottoman Turks didn’t twig to the withdrawal but rightly claimed a great victory.

Why did the Entente powers suffer this snafu (military acronym for major stuff-up)? The major contributing factors were:

- Poor and hasty planning. The Gallipoli landings were actually the campaign's ‘Plan B'. In mid-March, Plan A was attempted – a British naval attack aimed at forcing a way through the Dardenelle straits and capturing Constantinople. It was seriously dealt to by the Turkish gun emplacements and mobile artillery on the peninsula and failed in its efforts. Yet, little over a month later, Entente Army units were being landed from naval craft on unreconnoitered shores beneath a steeply-hilled terrain which the Turks had fortified. In the dark and with tides having not been sufficiently taken into account, the Anzacs ended up landing a mile further north than was intended, at what became known as Anzac Cove. Both landings suffered heavy casualties and could only establish toeholds which in the end, despite much heroism and bravery, were unable to be expanded.

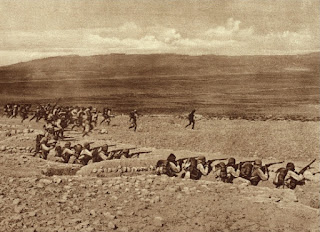

- Underestimation of the enemy's prowess. The campaign's planners thought that because the British had earlier defeated the Ottoman Turks in Mesopotamia, they would be 'easy-beats' in Gallipoli. That first battle was against conscripts from Iraq. The Gallipoli peninsula, however, was defended by experienced Anatolian Turks who were protecting their homeland from invasion. Capable German and Turkish officers were in command (including Mustafa Kemal, who went on after the war to found modern Turkey). The Turks held the high ground, fought ferociously and the Entente land forces could not dislodge them for any length of time.

- Atrocious conditions. The toeholds gained by the Entente troops were insufficient for supplies to be stored, waste to be disposed of and bodies to be buried. Wounded soldiers had to be ferried back to naval ships waiting offshore. Infestations of rats and lice broke out and dysentery was rife, spread by huge swarms of flies breeding on the unburied corpses.

|

| Turkish soldiers fighting at Gallipoli. Credit: Canva |

Today, in and around Trentham Camp, there are permanent reminders in the form of street names of those terrible World War One battles - Anzac Drive, Messines Avenue, Suvla Road, Gallipoli Road, Somme Road, Gaba Tepe Way. Each year on the 25th of April, New Zealanders and Australians pay special homage to those who died in war. We wear red poppies (as abundant on the hills of Gallipoli as they were in Flanders’ fields). Local communities mount street banners with poppy emblems on them, and memorial services are held throughout each country and in other countries, including Turkey. The day is known as Anzac Day.

|

| Poppy banner, Lower Hutt, April 2024 Image: Keith Westwater |

No comments:

Post a Comment